Finding things wrong with the US medical system is like dynamiting fish in a barrel.

Finding ideas for improvements isn’t any harder.

Implementing such ideas or even simply validating whether they are good ideas is much, much harder.

But one day I stood back and considered the “system” while keeping in mind three little phrases.

1) Who cares? It’s not my money.

2) You get what you pay for.

3) First, do no harm.

There may be other phrases as pithy and relevant. I don’t know. Can you think of any?

Let’s flesh these phrases out:

Who cares? It’s not my money.

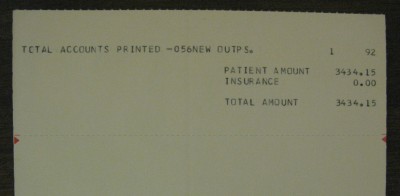

Medical expenses are disconnected between payer and payee. Given regulatory realities, if you want to control your own medical expenses, you need a competing system – in another country.

But, going to another country is not often an option. US medical expenses are dominated by Medicare/Medicaid. Medicare/Medicaid don’t pay foreign medical bills.

When you are insulated from the price of medical care, your are not the customer. You are the product, perhaps. The raw material, perhaps. But you are not the customer.

Imagine buying something from Mr. Someone without knowing the price until your bank account has been debited for that Wells Fargo money order you sent to Mr. Someone. Ah, you would be the “mark”, perhaps, but not the customer.

You get what you pay for.

We all deeply know that “cheap” is cheap and “expensive” is high quality.

When you are sick or broken, do you want a cheap fix? Gosh no! You want the best money can buy. Since you have no clue what particular fix you want, it’s safest to go with the expensive fix and hope for the best.

Just try to justify a cheap fix for someone else’s body. Don’t you look horrid? Yes, you do, you uncaring cheapskate.

So, the existing medical system is a cost maximizing system. By demand.

First, do no harm.

Medical practice is not perfect. Many diseases and other negative attributes of our bodies are not dealt with well at all. This will always be true.

So how does the “system” find cures or fixes?

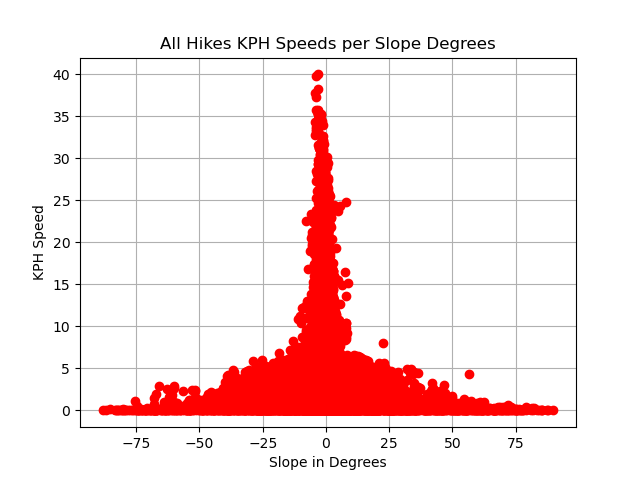

Carefully. By “hill climbing”.

“Hill climbing” is a simple, universal search method. When hill climbing, you start from where you are and look around your neighborhood for a better place to be. You go to that place and do the same thing again. And again. And again. Until you find yourself in the best place in your neighborhood. You have found what you are looking for. Search complete.

For example, imagine looking for a cure for cancer.

You have a current therapy for cancer. But is there a better one?

Well, you *could* search for one by randomly trying all sorts of things:

* Homeopathic beets.

* Up-beat music.

* Vegetarian fish.

* And so on.

But, “First, do no harm.” Ignoring the current, best therapy can certainly qualify as doing harm. So, to find a better therapy, you modify the current, best therapy by just a very little. Usually, you add something to the current best therapy – an extra “medicine”. Just enough to check a similar, nearby therapy. Carefully. Then, if this new therapy is an improvement, you switch to it, and do the process again. Carefully.

As a strategy, hill climbing can work very well. Unless the possibilities are vast or the best therapies don’t have wide, easily found slopes leading up to them.

Hill climbing gets stuck on what are called “local maxima” – the best place in the vicinity. Not the best place. Only the best place near the searcher’s current location.

Hill climbing is not a good way to find breakthroughs. Breakthroughs happen when someone gives up on current practice and flies off on a tangent. Doing harm.

Consider ants when they know their food source. They file to and fro, slightly improving the path to the source by cutting corners until the path is short and easy. They do no harm.

When the path is broken, the ants wander around in a peculiar random way, casting about for some indication of food.

They can die wandering randomly. “Tough break, Mr. Ant. Hard times call for hard measures. You do yourself harm for the greater good.”

Uh, huh. Sell that to Hippocrates and his oath.

So there you have it. Food for thought.